Lec1

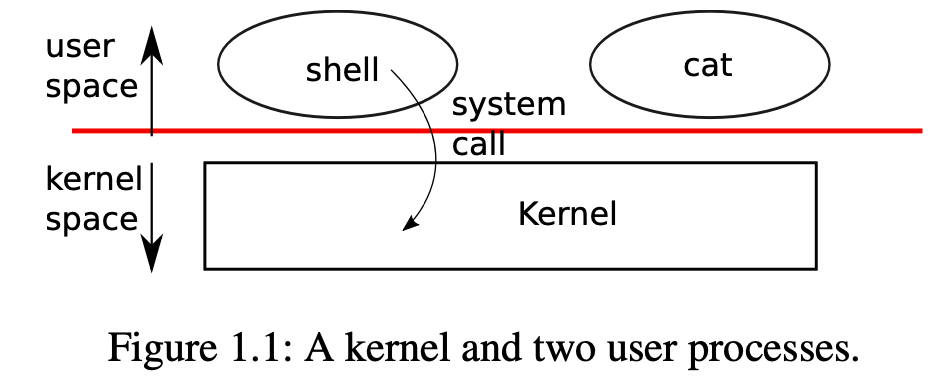

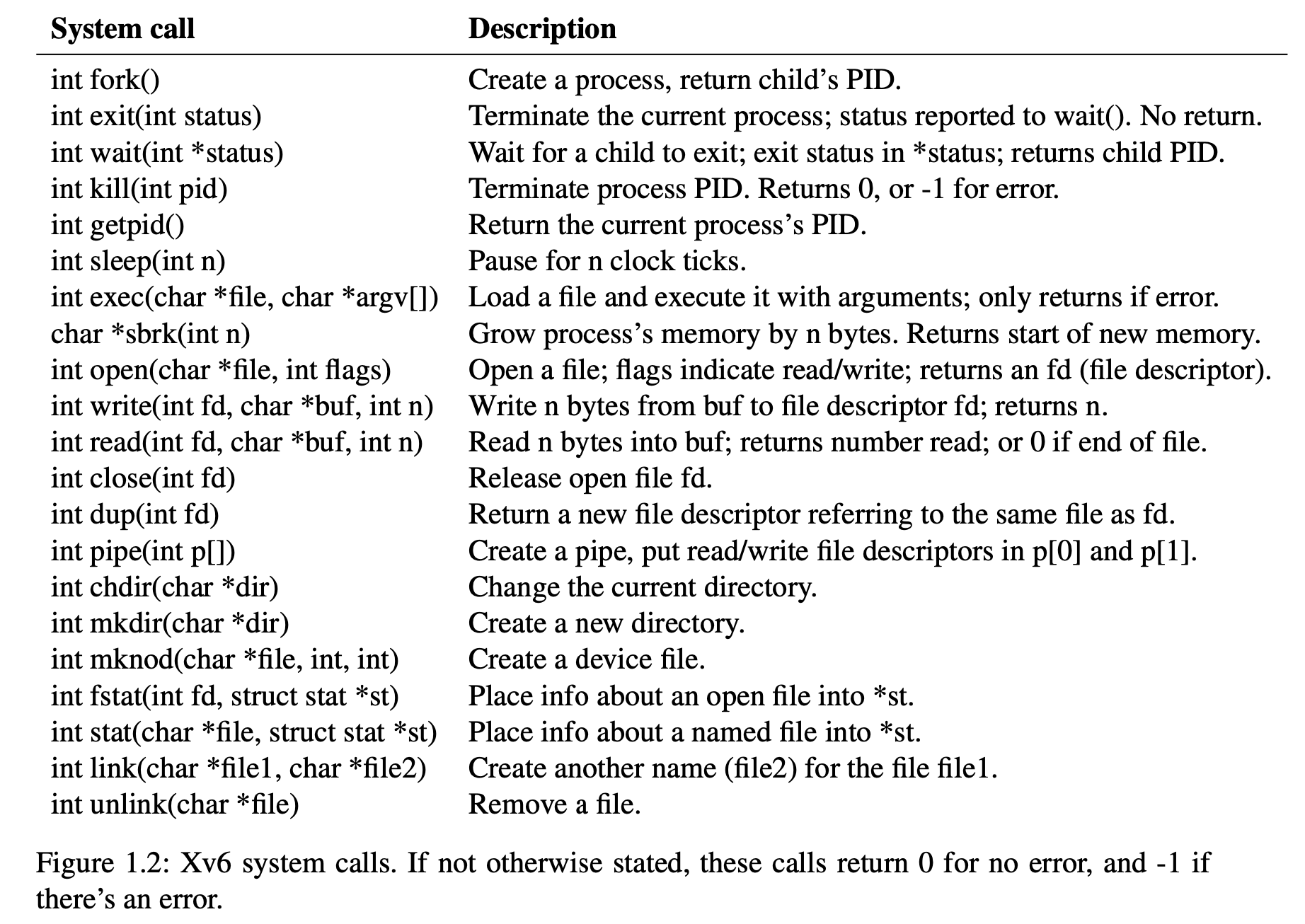

1. Preparation:Operator system interfaces¶

book-riscv-rev3 Chapter1

1.1 Processes and memory¶

- An xv6 process consists of user-space memory (instructions, data, and stack) and per-process state private to the kernel.

- A process may create a new process using the

forksystem call.

- If

execsucceeds then the child will execute instructions fromechoinstead ofruncmd. At some pointechowill callexit, which will cause the parent to return fromwaitinmain(user/sh.c:146). - why

forkandexecare not combined in a single call; we will see later that the shell exploits the separation in its implementation of I/O redirection. To avoid the wastefulness of creating a duplicate process and then immediately replacing it (withexec), operating kernels optimize the implementation offorkfor this use case by using virtual memory techniques such as copy-on-write (see Section 4.6). - Xv6 allocates most user-space memory implicitly.

1.2 I/O and File descriptors¶

- A file descriptor is a small integer representing a kernel-managed object that a process may read from or write to.

- the file descriptor interface abstracts away the differences between files, pipes, and devices, making them all look like streams of bytes. We’ll refer to input and output as I/O.

- By convention, a process reads from file descriptor 0 (standard input), writes output to file descriptor 1 (standard output), and writes error messages to file descriptor 2 (standard error).

- the shell exploits the convention to implement I/O redirection and pipelines. The shell ensures that it always has three file descriptors open (user/sh.c:152), which are by default file descriptors for the console.

- The

readandwritesystem calls read bytes from and write bytes to open files named by file descriptors. - The use of file descriptors and the convention that file descriptor 0 is input and file descriptor 1 is output allows a simple implementation of

cat. - A newly allocated file descriptor is always the lowest-numbered unused descriptor of the current process.

- The system call

execreplaces the calling process’s memory but preserves its file table. This behavior allows the shell to implement I/O redirection by forking, re-opening chosen file descriptors in the child, and then callingexecto run the new program. - The parent process’s file descriptors are not changed by this sequence, since it modifies only the child’s descriptors.

- The second argument to

openconsists of a set of flags, expressed as bits, that control whatopendoes.- like:open("input.txt", O_RDONLY)

- Now it should be clear why it is helpful that

forkandexecare separate calls: between the two, the shell has a chance to redirect the child’s I/O without disturbing the I/O setup of the main shell. - Although

forkcopies the file descriptor table, each underlying file offset is shared between parent and child. - The

dupsystem call duplicates an existing file descriptor, returning a new one that refers to the same underlying I/O object. Both file descriptors share an offset, just as the file descriptors duplicated byforkdo. - a process writing to file descriptor 1 may be writing to a file, to a device like the console, or to a pipe.

1.3 Pipe¶

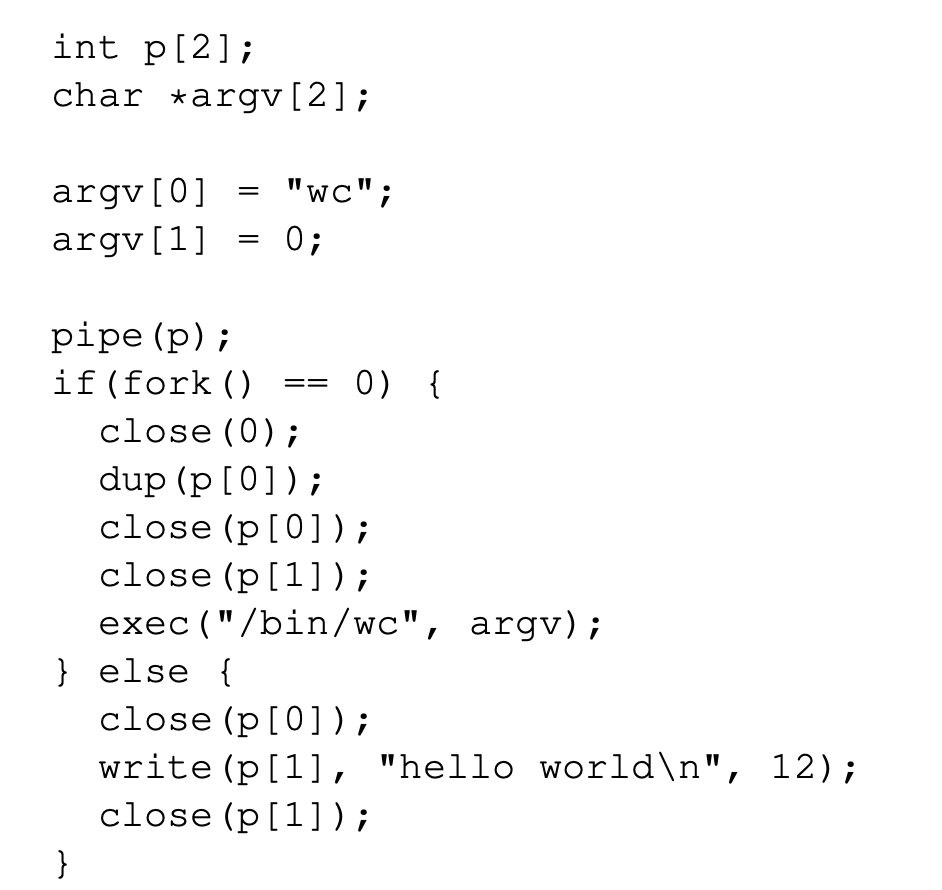

- A pipe is a small kernel buffer exposed to processes as a pair of file descriptors, one for reading and one for writing. Writing data to one end of the pipe makes that data available for reading from the other end of the pipe. Pipes provide a way for processes to communicate.

- If no data is available, a

readon a pipe waits for either data to be written or for all file descriptors referring to the write end to be closed. - The fact that

readblocks until it is impossible for new data to arrive is one reason that it’s important for the child to close the write end of the pipe before executing wc above - (e.g.,

a | b | c) the shell may create a tree of processes. - Pipes may seem no more powerful than temporary files: the pipeline

echo hello world | wccould be implemented without pipes as `echo hello world >/tmp/xyz; wc